Originally trained as an experimental physicist in undergrad, I slowly gravitated to biology – and eventually neuroscience – through my work studying the biomedical applications of organic and nanomaterials at George Mason University (plus a brief stint studying gamma oscillations in a neurophysics lab out at UCLA). Once in graduate school at Princeton, I leveraged my mathematical and computational training from physics to ask questions about the dynamics of neural activity and behavior. Using statistical methods and machine learning, I identified patterns in how a mouse’s behavior evolves over time as it uses different strategies to make decisions. Thanks to optogenetics, I was also able to uncover the role of specific brain regions in driving those strategies. Eventually, I expanded on those methods in applications to more complex behavior and in better and faster inference techniques.

Graduate school left me with a keen interest in complex dynamical systems and, more fundamentally, time: How does the brain change over time? What are the underlying neural dynamics that elicit observable changes in behavior or cell populations? What are the patterns and “states” that the brain fluctuates between as a result of changing environments, motivations, and even disease?

This last point has become the focus of my post-PhD work. Pushing myself towards more translational questions and returning to the root of my interest in biomedicine and biotech, my research agenda at the Allen Institute is about understanding the dynamics of disease. What are the genetic changes that drive neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease? Are there patterns in those changes attributable to differences in cell type? Could we ask these same questions about neural development? On a shorter timescale, how does learning — a distinctly dynamic process — differ in mice with symptoms of autism spectrum disorder compared to neurotypical animals? Might we identify correlates of those dynamic differences in the neuromodulatory signaling of brain regions associated with learning? These are the questions that motivate my current work, along with the hope that answering such questions will shed light on neurological interventions that can rescue healthy and more functional brain states.

Fellowship Research

Dynamics of neurological diseases and disorders

Check back soon once I’ve had time to actually write something detailed about my current work!

PhD Research

Quantitative modeling of natural behavior in rodents

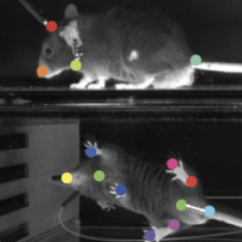

With the help of behavior tracking software like DeepLabCut and SLEAP, the quantification of natural behavior has become an increasingly popular area of study in neuroscience. However, how to best take high-dimensional measurements of behavior (such as joint positions or pixel data) and identify interpretable, low-dimensional representations (i.e. “syllables” of behavior such as walking or grooming) from that data is still an open question. This is an important line of research not only because it can help with the automated, unsupervised identification of behavior in a variety of animals, but also because it can help map these behaviors to changes in neural activity as observed in electrophysiology, calcium imaging, and other types of neural data. Latent variable models are a powerful tool for addressing these challenges, and I touched on one such approach, using switching linear dynamical systems (sLDS) methods, in my thesis.

Spectral learning of Bernoulli linear dynamical systems models

Accurately identifying the parameters of generative models like linear dynamical systems (LDS) can be a complicated process involving the use of time-consuming and computationally-intensive methods such as the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. Therefore, fast methods for approximating these parameters — either to a satisfactory degree of accuracy or for use as intelligent initializations in optimization techniques like EM — can provide great advantages in the use of LDS models. Here, we develop a spectral learning method for fast, efficient fitting of input-driven Bernoulli LDS models that extends traditional subspace identification methods and is ideal for application to binary time-series data that are common in neuroscience, such as choice behavior in two alternative forced choice (2AFC) decision-making tasks and binned neural spike trains. paper code

Latent variable model of decision-making strategies in mice

When mice make decisions, do they use the same strategy trial after trial, or do they switch strategies over time? What brain regions are involved in this possible strategy-switching behavior? In this project, I applied a hybrid model consisting of a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) and a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to behavioral data of mice performing a two alternative forced choice (2AFC) decision-making task while receiving optogenetic inhibition of either the direct (D1) or indirect (D2) pathway of the dorsomedial striatum (DMS) on a subset of trials. We found that not only do mice use different strategies when making decisions (guided by different external and behavioral variables such as the task stimulus or previous choice), but that the role of the DMS in decision-making is strategy-dependent. paper paper code

Undergraduate Research

How hippocampal gamma oscillations encode running speed

During undergrad, I spent a summer working at UCLA as part of an NSF-sponsored Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). There, I analyzed local field potential (LFP) data, looking at high frequency (gamma, 30-140 Hz) oscillations in the hippocampus of rats while running mazes in both the “real world” and virtual reality (VR). The goal was to compare what type of cues (e.g. distal, self-motion, vestibular, and sensory — only the former two of which are present in VR) are responsible for modulating gamma rhythms. We also explored how changes in theta phase and phase precession could contribute to this modulation. Our results suggested that two categories of gamma oscillations – slow gamma (30-60 Hz) and fast gamma (60-140 Hz) may have distinct roles in encoding running speed, with different sensitivity to environmental cues.

Characterizing the optoelectronic properties of nano-materials

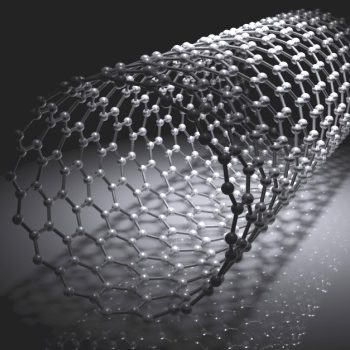

As a physics undergraduate, I worked with Dr. Patrick Vora on a variety of projects exploring the optical and electronic properties of low-dimensional materials. This included studies focused on identifying the stoichiometry, morphology, and charge transfer properties of organic materials for use in biomedical devices; assessing the optical absorption properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) when coupled with dopamine for use in real-time neurotransmitter sensors; and discovering new 2D materials (e.g. transition metal dichalcogenides, or TMDs) for use in next-generation electronics. paper paper paper